II n′y a pas de Youkali

Is Berlin still a place of free speech, “wo die Verrückten sind?”

Youkali, c’est le pays de nos désirs

Youkali, c’est le bonheur, c’est le plaisir

Mais c’est un rêve, une folie

Il n’ya pas de Youkali

Youkali, the land of our desires.

Youkali, it is happiness and pleasure,

But it is a dream, a folly.

There is no Youkali.

KURT WEILL/ROGER FERNAY (unknown translation)

These past few weeks have not been the easiest for the cultural sector in Germany. On Friday, November 17th, the Documenta committee, responsible for curating one of the biggest art exhibitions in Europe for its next edition in 2027, resigned in its entirety after receiving news that one of its six members, Indian curator, art critic and poet Ranjit Hoskote had himself resigned due to the controversy raised from his signing a 2019 statement by the boycott, divestment and sanctions movement (BDS), a group designated as antisemitic by the German parliament in 2019.

Earlier in the month, the member of the parliament in Berlin-Neukölln Susanna Kahlefeld (Greens) had pressured the Senate Department for Culture and Europe to review the funding of arts and cultural centre Oyoun in the same district, due to its refusal in cancelling an event on the evening of November 4th, namely a memorial service held by the association Jewish Voice for a Just Peace in the Middle East. Both the event, and by extension Oyoun, were labelled by Culture Senator Joe Chialo (CDU) with "hidden antisemitism". This led to the Senate terminating funding to Oyoun on November 20th, in an unprecedented decision that could affect artistic freedom, as well as freedom of speech all over the country.

As there are already many op-eds and columns in press and online media discussing the rise of antisemitism in Germany, as well as others that question the conflation of criticism of Israel with antisemitic views, or those that demonstrate how a pro-Israel political consensus has been shutting down dissenting voices, I would like to propose that the current text goes in a different direction. For that, I’ll do a quick excursion into the song “Youkali” by German-American composer Kurt Weill (1900–1950).

A longing for a place that can only exist in imagination, but that is grounded in the very human feeling of hope and yearning for happiness and pleasure is perhaps most beautifully translated in northern European art, in my opinion, through the soul-wrenching “Tango Habanera” (1934), with music by Kurt Weill, that later became the celebrated art song “Youkali” (1946), with lyrics by French actor, poet and songwriter Roger Fernay (1905–1983). Written during Weill’s exile in France, a Jewish musician famous for his collaborations with German theatre practitioner, playwright, and poet Bertolt Brecht (1898–1956), after fleeing Germany in 1933 with the rise of the Nazi party to power, that song was initially incidental music composed for the 1934 play Marie Galante, which premiered on December 22nd of that same year at the Théâtre de Paris, adapted from a novel by French playwright, screenwriter and film director Jacques Deval (1895–1972), stage direction by H. Henriot.

It was only in 1946, nevertheless, that the now world-renowned lyrics by Fernay were added to the song, giving it its renewed poetic meaning for the mythical land of Youkali, a place for happiness and enjoyment, for light-heartedness and zest for life. Perhaps it was in Weill’s own borderlands subjectivity and artistry that such a poignant song came to be: exiled for almost three years in France, he arrived in New York City on September 10th, 1935, aboard the S.S. Majestic with his wife, Austrian-American actress and one of the most important interpreters of the Brecht/Weill musical theatre repertoire, Lotte Lenya (1898–1981). It was in this transcultural life in exile that Weill was able to revolutionise U.S. American theatre and help create Broadway’s distinct style of musical plays. He did not achieve incredible success on the North American stage, however, until 1941 with his musical Lady in the Dark, lyrics by Ira Gershwin (1896–1983), book and direction by Moss Hart (1904–1961).

“Youkali”, despite Kurt Weill’s box-office hits on stage and film, remained largely unknown to the public until Lotte Lenya passed the baton as Weill’s prestige interpreter to Canadian operatic soprano Teresa Stratas in November 1979, after watching the singer perform Jenny at the Metropolitan Opera’s first performance of Brecht/Weill’s Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny (Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny, 1930). By sharing with Stratas a collection of unpublished songs, which Lenya had kept tightly guarded after Weill’s untimely death, caused by a heart attack shortly after his 50th birthday, the Brechtian star facilitated the creation of Teresa Stratas’s absolute album The Unknown Kurt Weill (Nonesuch Records, 1983), recorded with piano accompaniment by North American conductor, pianist, and composer Richard Woitach (1935–2020). This record, which featured a splendid and unique rendition of the tango habanera, would later contribute to Weill’s musical popularisation by other well-known and diverse artists such as Ute Lemper and Anne-Sophie von Otter.

The beautiful lyricism of this song translates in artistic and philosophical form the utopian and borderland quality that I wish to develop this text further. Much like what Kurt Weill must have felt when composing that song, and by choosing it to be versed not in his native German language, but in French, the experience of exile seems to have been, for him, a largely important foundation for the creative representation of the post-World War II sentiments on despair and lack of faith in humankind.

Youkali, “the land of our desires”, is apparently the enchanted reality which many queer people like myself have chosen for their storytelling, in order to escape the grey and strenuous confinements of the disciplinary heteronormative patriarchy, cemented on the whiteness construct and on capitalist individualism as ruling life experiences. I call to mind, in this moment, the statement from Jamaican black activist Marcus Garvey (1887–1940) on how “a people without knowledge of their past history, origin and culture is like a tree without roots”.

End of excursion. Back to Berlin, November 2023.

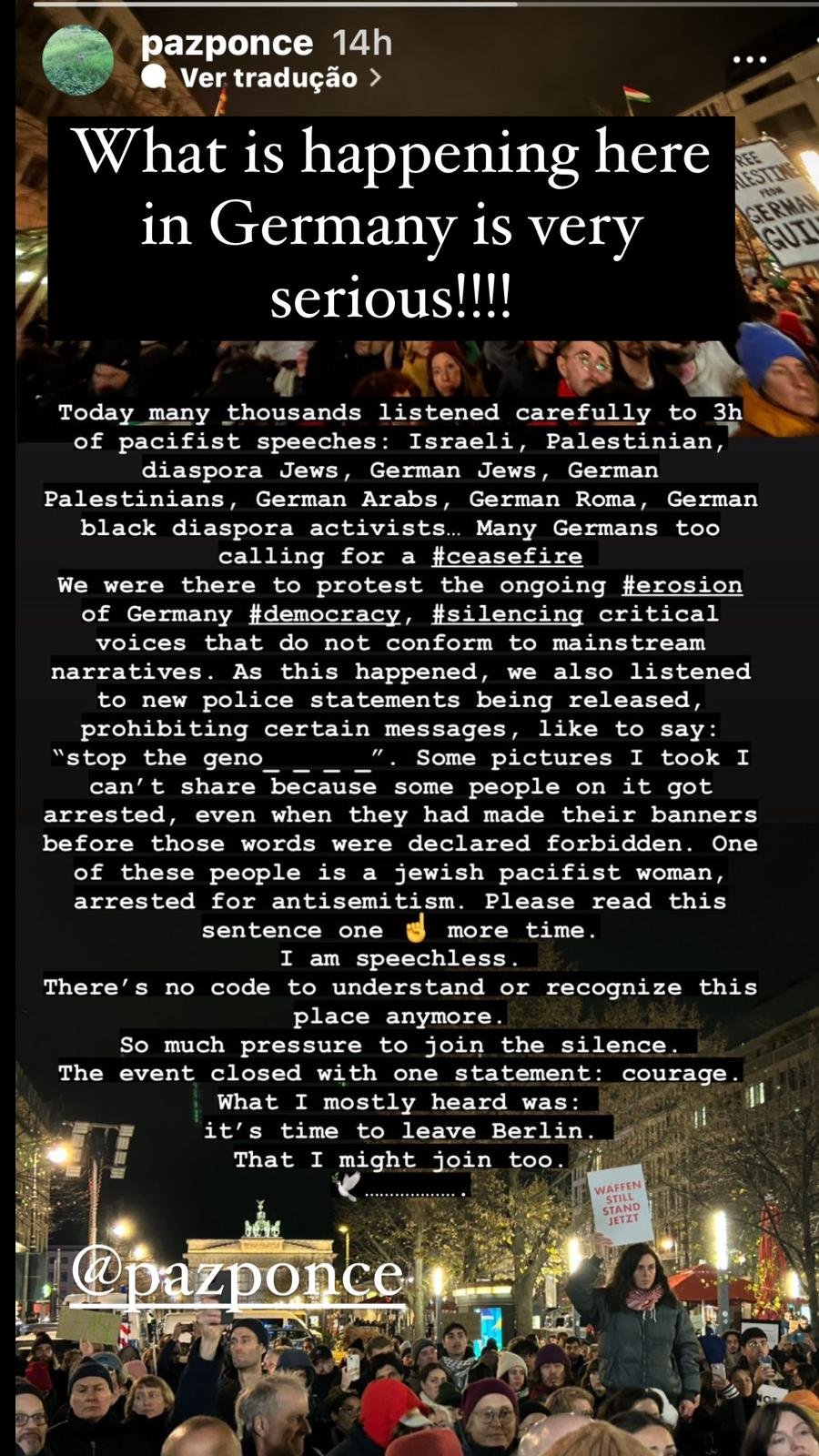

Image Description: An Instagram Stories screenshot from a protest in the city of Berlin, Germany, is depicted in a picture in front of the Brandenburg Gate. On the top right corner, a sign being held by someone is visible, and reads: "Free Palestine from German Guilt”. On the bottom right corner, a woman standing higher from the rest of the crowd holds a sign that reads “WAFFENSTILLSTAND JETZT” (Ceasefire). In front of the picture, on the top, there’s a text written in white font over a black highlight that says: “What is happening here in Germany is very serious!!!”. Standing in front of the picture, in the center, there’s a body of text in white font over black highlight that reads: “Today many thousands listened carefully to 3 hours of pacifist speeches: Israeli, Palestinian, diaspora Jews, German Jews, German Palestinians, German Arabs, German Roma, German black diaspora activists… Many Germans too calling for a #ceasefire. We were there to protest the ongoing #erosion of Germany (sic) #democracy, #silencing critical voices that do not conform to mainstream narratives. As this happened, we also listened to new police statements being released, prohibiting certain messages, like to say: ‘stop the genocide (full word has been redacted with a black highlight)’. Some pictures I took I can’t share because some people on it got arrested, even when they had made their banners before those words were declared forbidden. One of these people is a jewish pacifist woman, arrested for antisemitism. Please read this sentence one (index pointing up emoji) more time. I am speechless. There’s no code to understand or recognize this place anymore. So much pressure to join the silence. The event closed with one statement: courage. What I mostly heard was: it’s time to leave Berlin. That I might join too. (dove emoji and a sequence of full stops)

Screenshot taken from @pazponce

Paz Ponce (Cádiz, 1985) is an art historian and works in Berlin as an in(ter)dependent curator, manager of art spaces and cultural networks between Europe and Latin America.

“It’s time to leave Berlin”. The city “wo die verrückten sind” (in contemporary language, something like “where the weirdos are”)—a verse from the marching song “Vorwärts mit frischem Mut” (forward with fresh courage) written by Franz von Suppé for his 1876 three-act operetta Fatinitza, which had its premiere in Vienna—has been historically known for its cosmopolitanism and acceptance. This has been, however, drastically changing, given the U-turn that the city, and Germany, have been making with regard to censorship and faulty freedom of speech. In this blog, I have already written on how Germany has been waging a silent war on sex workers, on how it has not really been keeping the best track record in its everyday dealings with racism, as well as in how it has been taking part in a semiotic war being waged globally.

Du bist verrückt mein Kind, You are freaky, dear

du musst nach Berlin. You have to go to Berlin

Wo die Verrückten sind You belong to where

da gehörst du hin. the freaks are.

FRANZ VON SUPPÈ (unknown translation)

Perhaps, much like in Kurt Weill’s song, instead of taking the literal meaning of its verse “Il n’y a pas de Youkali” (“there’s no Youkali”) as an assertion of denying utopias and illusions, its poetic semantic might reveal there is actually a possibility for a certain “presentifying" of utopianism: no time is better for change and actualisation than now. In denying the real existence of Youkali, Weill creates the very possibility of engendering an other world: one which not only we are able to conjure with our imaginative power, but also one in which we can assign meaning according to our desire.

In my own Umwelt, as Jakob Johann von Uexküll (1864–1944) defined one’s private world in his theory for living beings’ subjectivity, I have also been pondering on whether to leave Berlin (and Germany), and this has long been reflected upon before the past months’ events. As the occurrences from the first paragraph of this text unfold, there is more urgency added to the feeling that Berlin is no longer fertile ground for wandering minds, idealists, and dreamers.

But by the time this text was made available online, Oyoun had already successfully raised over 30% of its intended 72.000 € goal to help pay for the high legal and court fees necessary for the reversal of the Berlin Senate’s decision. This was in part achieved by favourable international press in France and the UK, as well as to a viral TikTok video by Lucas Febraro, a Brazilian-born Berlin resident and Director Of Communications at Democracy in Europe Movement 2025 (DiEM25), which has garnered over half a million views. So far, the crowdfunding campaign has earned financial support from members of the public sphere such as Belgian-born artist based in Rotterdam Reinaart Vanhoe, Palestinian-British film director Omar Al-Qattan, Berlin-born visual effects supervisor Bastian Hopfgarten, among others.

……………………………………………………………………………………………..

As I am walking home in Neukölln, carrying two heavy boxes containing music stands that the DHL had not delivered directly to me, I had a brief moment of cross-cultural allyship that I decided to include here. I do not wish to make myself a victim, as it was fully my choice to carry these two heavy boxes between the 550 metres between the DHL shop and my apartment. However, as I walked down Hermannstraße early in the evening on a Saturday, I was shocked to see how uncivil some of the people were, even whilst watching me struggle to carry these two heavy boxes. A US-American white couple passes me by, and they look at me begrudgingly for taking too much space on a large sidewalk, while making frivolous conversation. A white German guy stands in front of me on the next block, staring at his phone, and not really seeming interested to notice or make way for the person walking behind—something that led me to utter some phrase of disbelief in Brazilian Portuguese. Finally, as I am 100 metres away from my building’s door, but nevertheless exhausted by this dramatic walk, I kneel down carrying both boxes for a moment to catch my breath, and another immigrant—like me—an Indian guy riding one of the bikes for delivery services, circles with the bike around me and asks me: “Hey, do you need some help? Where’s your house? You can put one of the boxes on top of the [delivery case on the] back of my bike”.

Is it time to leave Berlin? Perhaps after moments like this, the answer can become a “maybe”.

Photo credit: © Amelie